Misled by intuition: how organizations achieve less, later, and at a higher cost

Overutilization and multitasking do not work, and here’s why.

Waiting

Waiting — what an interesting word. Translated into Latin it’s exspectans. As if we’re expecting something great to happen, anticipating with suspense and a bottle of champagne.

In reality? Waiting is more about Americans spending 37 billion hours in lines by every year, and 47 days queuing over the course of the lifetime for the British. Little of which is filled with excitement.

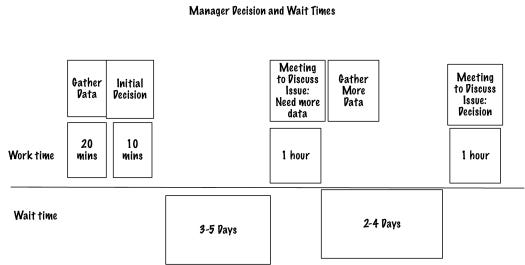

We know waiting from work too. It’s a magic trick that makes five-minute decisions take two weeks, and causes project delays. Waiting means less and later.

Typical solutions across companies big and small? Overutilization and multitasking.

Overutilization — productivity theater = measuring productivity by hours worked and treating any idle time as a gap to fill in with any work. The goal is to keep everyone 100% busy, the what is secondary. Let’s optimize our resources!

Multitasking — if doing one project will deliver value, then doing two projects must deliver more value. Let’s do another project!

Both are based on an intuitive assumption that the more we work the more we get done, and both are wrong. Organizations often suffer from what we can call a quicksand syndrome.

A quicksand syndrome

Once in quicksand, we want out quickly, so we act quickly. But the faster and more we move the deeper we sink.

In order to get out, we must do the opposite of what the intuition tells us — take a few steps backward, lean back, move slowly and deliberately, keep pulling ourselves until we’re out.

Let’s let that sink in: overutilization and multitasking do not work. We get less, later and at a higher cost, and here’s why.

I. Overutilization — busyness by design

How to unlock a traffic jam?

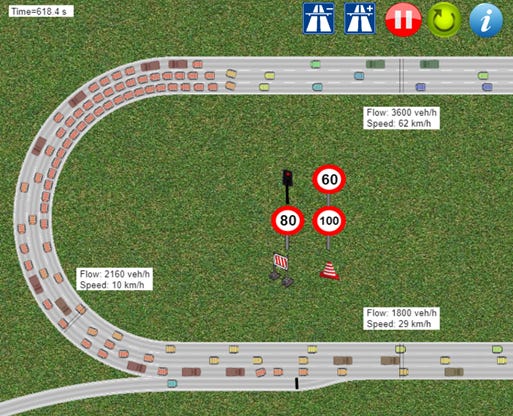

Traffic jams. If you have ever been stuck in one, you have experienced the impact of overutilization on flow. Too many cars on the road = overutilization = the system as a whole is slower.

Once the utilization of the road goes above about 80 percent, the speed of the traffic starts to slow down.

Here’s how the traffic works exactly — give it a go with the traffic simulation:

How can we unlock a traffic jam then?

by having a policeman walking among the cars and telling drivers to go faster

by putting more cars on the road

by limiting the number of cars on the road

Even though we know the answer (yes, it’s 3.), we do the opposite at work. We have managers motivating their teams to work harder, and when requests get stuck, we add even more requests to expedite the previous ones. And so the vicious circle continues.

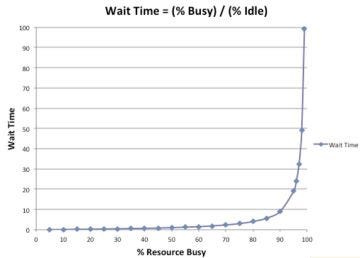

a) The busier we are, the longer we make each other wait

Imagine you need 5 minutes of one person’s time for a review. Based on your experience, how long will you need to wait? An hour? A day? A week?

We can calculate wait times thanks to Little’s Law.

Let’s say you work 50 hours a week and are busy for 48 hours (That is 96% busy, 4% idle). How long does it make others wait for you?

Wait time with Little’s Law: 48 / 2 = 24 hours = 3 working days.

That’s how long others will need to wait on average to get an hour of your time. If you have only an hour free instead of two? The wait time doubles to 6 working days, which really means two weeks!

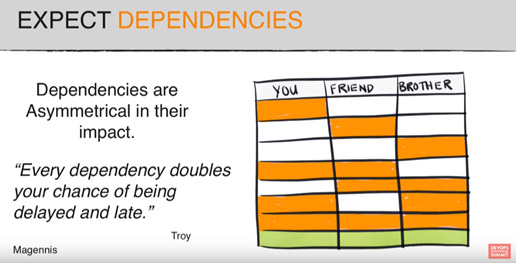

b) The more we depend on others, the worse it gets

Now imagine we need 3 people for a sign off meeting. What is the likelihood that they will all be available for 1h of work at the same time and come on time? Domenica Degrandis described it really well in her talk “Making Work Visible: How to Unmask Capacity Killing WIP — Dominica DeGrandis”

When we depend on three people, there is only 1 in 8 chance of all being on time, and 7/8 of a chance of being delayed. If we had difficulties with the availability of one person, good luck to us with the availability of three.

c) Overutilization leaves no room for the unexpected, including escalations.

Things happen. We need to have some space to accommodate the variability, which is a given in knowledge work. Overutilization is like tailgating. There is very little margin of error if the car in front of us behaves unexpectedly. Why risk it? Did you hear of Google allowing their employees to spend 20% of the time on personal projects? Now you know why.

II. Multitasking — the best way to stay busy and get less done.

a) Multitasking is expensive.

Multitasking is going to slow you down, increasing the chances of mistakes. (…) Disruptions and interruptions are a bad deal from the standpoint of our ability to process information — said David E. Meyer, a cognitive scientist in the interview with the NY Times. As scientists indicate, multitasking is really a rapid task switching.

The consequences of multitasking are:

Delays — context switching from one task to another, the leading multitasking tax component, requires extra time — it takes an average of 23 minutes and 15 seconds to get back to the original task.

Weaker analysis skills due to inability to filter irrelevant information

Hindered learning — as Neuroscientist Daniel Levitin says “Students who uni-task, immersing themselves in one thing at a time, remember their work better, get more done, and their work is usually more creative and of higher quality.”

And yet, we keep doing it.

b) Multitasking can bring some benefits for only up to two items

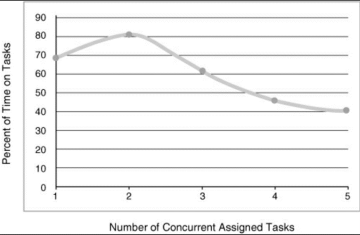

Yes, multitasking might work in the organizations, but up to a point of two items. Mike Cohn wrote in the Agile Estimating and Planning:

Clark and Wheelwright (1993) studied the effects of multitasking and found that the time an individual spends on value-adding work drops rapidly when the individual is working on more than two tasks.

Logically, it makes sense that multitasking helps when you have two things to work on; if you become blocked on one, you can switch to the other. (…) if we’re working on three or more concurrent tasks, the time spent switching among them becomes a much more tangible cost and burden.

Now, what is the common practice in organizations? How could organizations ensure that not too many concurrent tasks or projects are being assigned? On the portfolio level.

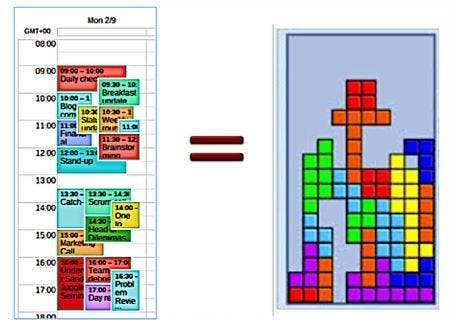

c) Resource Optimization’s Best Friend: Multitasking on the portfolio level = more projects and less value delivered later

When people do multitasking, it is called multitasking. When an entire organizations does it, it’s called portfolio management.

“But we can’t let our resources just sit and do nothing.”

As a Portfolio Manager responsible for resource allocation, what would you do if you had one person busy 50% of the time and another 80% of the time till the end of the year? Find them something else to do. We love utilization as a metric after all. And that is how we do it today.

It’s like with budgets. If we don’t spend it all we get less next year. If we exceed the sales target for the year, will we get lower ones next year?

Multitasking makes 100% resource allocation so much easier.

Building delays in with allocation Tetris

d) There is no value from started but unfinished work.

We like starting the work. The excitement at the beginning of the journey, the freshness, the abundance of business opportunities out there… Yet, four wheels with no engine will not make a car. Even forty wheels more will not make any difference. Still no car.

It’s like with reservations as explained by Jerry Seinfeld:

Is that so? Let’s compare two scenarios and find out

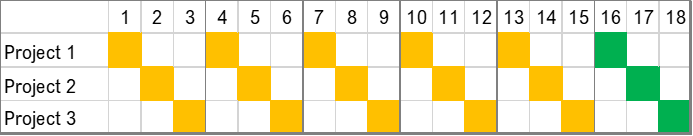

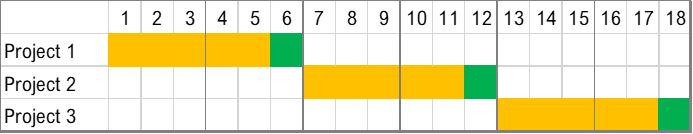

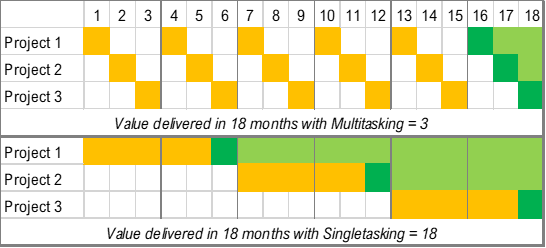

Let’s look at an organization that would like to deliver 3 projects — each requiring 6 units of work to be completed, each unit represented by a box.

Scenario 1: Multitasking with shared resources — doing a bit of every project = first project done after 16 months

Scenario 2: Single-tasking — finishing a project, before starting another. The first project was done after 6 months, 2nd after 12.

Starting sooner clearly does not mean ending sooner. In addition, it’s worth considering the value delivery. As Domenica Degrandis put it in here book Make Work Visible:

Business value that could have been realized sooner gets delayed because of too much WIP. This is known as cost of delay. It’s a concept used to communicate value and urgency — a measure of the impact of time on the outcomes we want, such as customers buying our product this month instead of next month.

This becomes clear when we consider value delivery for the scenarios discussed. As marked by the light green area, notice all the value delivered vs missed in the multitasking scenario:

Summary: Five things organizations can do to achieve more, faster, and at a lower cost

If not multitasking and overutilization, then what else can we do?

1) Make work visible

It’s difficult to manage something we do not see. One of the best ways to make work visible is Kanban — one of the key principles of lean and agile that can improve how we work day-to-day.

Use shared to-do’s based on the kanban board which has many benefits — kanban lets you see at what stage each item is, and where bottlenecks are. Here are some Kanban board examples to get you started. Microsoft Planner or Trello are just two of many tools available

2) Limit Work in Progress — single task

by adding a limit for work in progress (one of the Kanban principles), you make work flow faster

For teams, it might mean not accepting new tasks above an agreed threshold until previous work is finished. Plus, some psychological safety to do so.

For portfolio, it might mean learning to say no to some opportunities. For now, or forever like Steve Jobs did when he’s shut down 70% of Apple products upon his return in 1997.

3) Don’t plan for 100% busyness, build slack in

Do not pack the calendar to the fullest, leave some room for the unexpected, allow for deep work and optimize for flow. Block your calendar if you need to.

4) Reduce the size of work deliverables

Deliver in smaller parts, rather than big bangs to enable faster feedback and learning. E.g. in portfolio review — smaller business cases reviewed every month, rather than annually, developing campaigns in two-weeks iterations, rather than quarterly.

5) Measure and learn

We cannot improve if we don’t know where we are today. Key metrics to start with are:

WIP (Work in Progress) — the number of work items started, but not finished — how much are we multitasking?

Cycle time — how long it takes a work item to be completed once it’s started — how long do things take? After a while, it can serve as a good indicator for when things could be delivered and if it’s in line with stakeholder expectations

Lead time — how long it takes a work item to be completed once it’s initially requested — how long do things really take? Is there a huge queue before we can start work?

Throughput — number of items finished in a given period of time — are we good at starting, or are we good at finishing the work?

Metrics are an invitation to reflect on how we did more objectively, and how we can improve. Start measuring these, and then establish a cadence for reflecting.

That’s it. All we need to do is act upon these and… wait. But this time for good things to happen — more work done, faster.

This article is part of the series on how organizations can make work flow with lean, agile and common sense, but not common practice. You might also like:

Productivity theater: why is busyness mistaken for productivity?

Busy is a decision at home. Busy is a design at work.

17 ideas from Lean & Agile to make Remote Work better

How might we make remote work work better and mitigate its adverse effects? Let’s turn to Lean and Agile principles for…